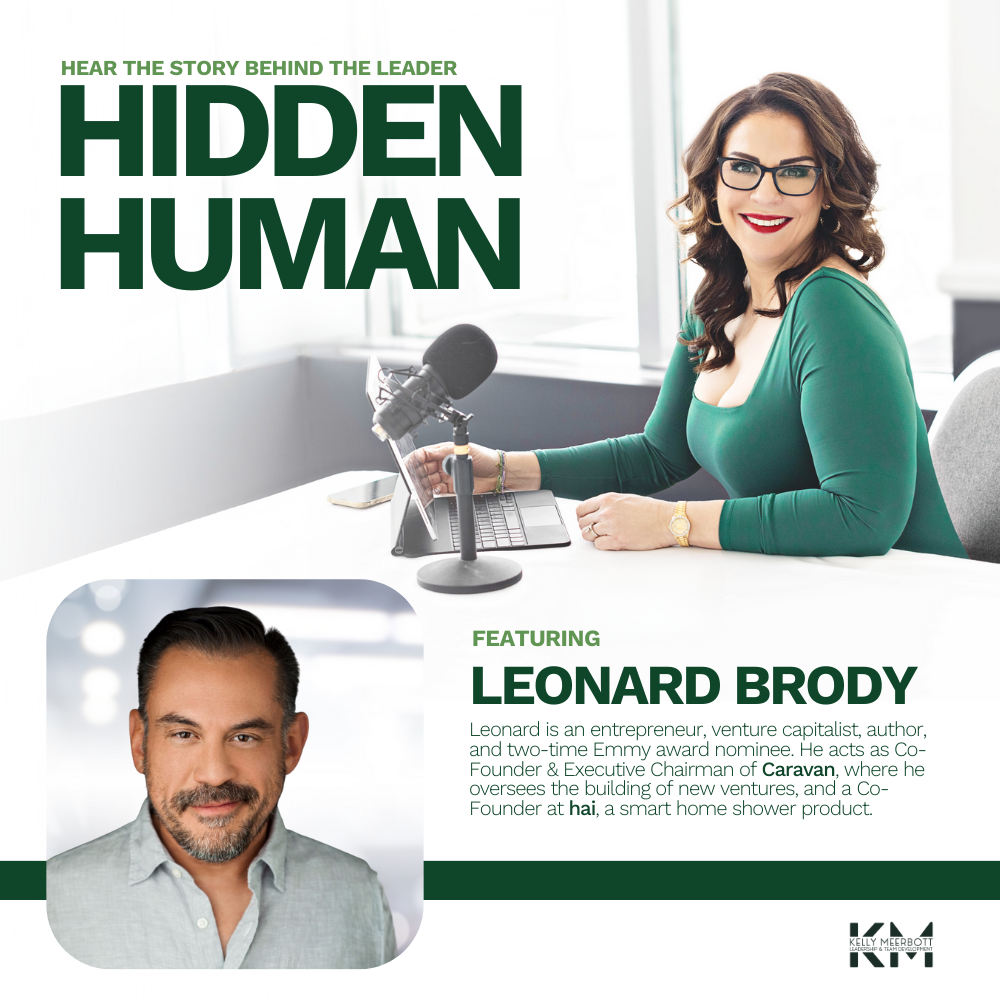

Join Kelly Meerbott and guest Leonard Brody as they discuss the media, entrepreneurship, and the power of resilience! Recorded July 10th, 2023.

Kelly:

Welcome to the space where we reveal our personal humanity to reconnect with our shared humanity. Let’s begin our conversation with Leonard Brody and Leonard, I will let you explain what your title is. And welcome to Hidden Human. We are so thrilled to have you here.

Leonard:

Thank you. I’m glad to have the opportunity. Appreciate you having me.

Kelly:

So if you were going to explain to me in a way I could understand if I were a six-year-old child what it is that Leonard Brody does in this world? What is it?

Leonard:

Well, I’m predominantly an entrepreneur and venture capitalist. So I’ve spent the last sort of 30 years of my life building companies at the intersection between consumer technology and media, okay, and today, I run and co-founded a joint venture with CAA Creative Artists Agency in Los Angeles, that co-founds really science-backed consumer companies with the most iconic people in the world. And that’s sort of what we do.

Kelly:

That’s incredible. So how young were you when this itch to build businesses came? And usually, what I find is usually that defining moment happens between the ages of eight and 14.

Leonard:

Yeah, that’s probably right with me. You know, I think, you know, when I was young, entrepreneurship wasn’t really accepted in the way that it is today. You know, I’m 52. And so, when I was in high school, and even in graduate school and stuff, there really was no training or that there was nothing interesting about being an entrepreneur, like I was graduating law school in 1997. So just at the time when HTML was surfable, the Internet, and Mosaic and browsers and stuff, were starting to come out. So the grand era of entrepreneurship was still in those days, kind of restricted to family businesses, and franchising and stuff like that. But I had the good fortune in my family of having a couple of people around me, that were family members that had been entrepreneurs, and been quite successful. And I just knew really young, that the idea of kind of sticking at a job and doing that path every day was just not in my blood. It just wasn’t for me. So I would say probably when I was 8-10 years old, I kind of knew that that’s really the path that I wanted to spend most of my days on.

Kelly:

What were the family businesses and who ran them when you were that young? Eight to 10? You know, and I would say you’re young at 52, as well, so, but eight to 10, who wasn’t your family? And what business did they run?

Leonard:

So the one that was probably the most impactful on me was a cousin actually, he was older. So we refer to him as an uncle, but his name was Israel Asper. And Izzy was really a force of nature as an entrepreneur, he ended up having an illustrious career, doing all kinds of things as a lawyer and as a politician. But he inevitably started what became Canada’s largest media company, television broadcaster, daily newspapers across the country, and then ended up being one of the largest television broadcasters in Australia, New Zealand, Ireland, Canada, and he was just an amazing person.

We have built a really nice relationship where we would write letters back and forth pre-internet, and I would see him at family events and you got a real sense from him about a) the work that was required to do this and b) how much intensity and part of your life it had to take to be able to actually deliver on being an entrepreneur. But I registered more with him and what he did, then family, friends who became lawyers, or people that ended up becoming dentists, or doctors and stuff that just for me, was never in my blood.

I do think, you know, having him around, was always a good Northstar to look and sort of see, you know, what, what does he do? And how did he do it? He unfortunately passed away many years ago, far too young. But I still find myself thinking, you know, like, what, what does he do? And how would he respond to this, and even in a day where it’s such a different economy than it was before, but I would say Izzy was really the driver for me.

I had lots of other people in my life that were uncles and cousins and stuff that all had. They were either lawyers, because I think back in that day, you know, back when I was in my 20s lawyers, really we’re more prone to be entrepreneurs than were MBA grads, because in that, in those days, the MBA grads were going into management, consulting and investment banking and stuff, they weren’t really thinking of entrepreneurship, whereas a lot of the lawyers were so a lot of our family that were lawyers ended up becoming entrepreneurial in some way or another small businesses or were otherwise. And so that’s kind of what drove me into it.

Kelly:

What do your mom and dad do?

Leonard:

So my father was a dentist, is a dentist and retired and my father and I are incredibly different. In a work respect, I think what attracted being a dentist to my father was the idea that you could sort of be at a set schedule, have a lot of free time, at the end of the day own your life. You know, it was small, I guess when you’re running a dental practice. It’s a small business in some respects, but it’s not. I think there’s a big difference, by the way, between running a small business and being an entrepreneur, I think they’re two very different things. And I’m happy to chat more about that.

But I was actually raised by a single mother, my parents were divorced when I was quite young. And my mom was quite entrepreneurial in her own right, or at least wanted to be entrepreneurial. So she always had little businesses that she was trying on the sides. I think in those days, it was quite hard for a single mother to gain full-time work. Talking in the late 70s, early 80s, I think it was much more difficult for her to find gainful full-time employment than it would be if she just did her own thing.

So she had a food delivery business where she would bake baked goods, probably illegally at home. And she would sell them to stores. She was a wholesaler for that kind of stuff. Then she had a couple of restaurants that she started that sort of began the process of her end up wholesaling. But she had a baking business.

Then she became a cookbook entrepreneur and has 10 best-selling cookbooks. But I think for her, she probably had it in her blood as well. But circumstances drove her into being an entrepreneur because I think it was just easier at that point. Ironically. Sure.

Kelly:

What qualities do you think you get from your mom? What do you get from your dad that you leverage in your work today?

Leonard:

You know, my mom. Look, my mom, my mom was a bit of a firecracker. And so she had,in some respects, had her own struggles with mental illness and other things that made it difficult for her. But my mother is incredibly resourceful. And I would say that that’s probably one of the most important skill sets for being entrepreneurs, understanding how to be resourceful. Like, in a business context, understanding that no doesn’t always mean No, and understanding how to work around corners and understanding how to get to a result you need in multiple different ways.

My mother was very, very good at that. And she was also a good salesperson, you know, she knew how to do it, she knew how to trigger people’s response that she wanted. And I think those were skill sets that the resourcefulness and that ability to sell were things that I really got from my mom. My dad is much more tempered, much more even keeled. And so I think I have a much more even keel than my brother for sure. But I would say from him, that even keeled kind of personality, it was something that was a good balance against what I learned because I spent most of my time with my mother.

So you know, behaviorally, you tend to adopt more of that when you spend more time with someone like that. So I think he helped balance that out. And my dad was more logical and rational than my mom. So it kind of balanced that out a little bit. And I think also, you know, my dad sort of changed his career path a little bit later in life, and how he wanted to practice dentistry.

It was a good lesson that you know, you can really, you have multiple chapters in your life and to your point, you know, while 50 May fino may feel old, in fact, it’s really just the beginning. It’s certainly for entrepreneurs, I would argue that’s your prime. Your prime is when you’re really in your late 40s to 60s, is when you’re really going to drive the vast majority of the energy and the revenue and the experience to be able to build something that’s significant.

Kelly:

What was your first job and I’m not talking about after law school, what was your very first job?

Leonard:

So because I was raised by a single mother, I worked very young, because my mother actually needed the income so I worked not because it went to me and I was buying stuff. It actually went to my mother and to the family, which is kind of like the 1930s kind of living like you were in 1930 but so much very first job actually, I was 11 years old. And we sold doughnuts door to door for a company called The Little devil donut company. And you basically got dressed up like a little devil. And I think they were like Dale doughnuts from a bakery. And this bakery just basically tried to figure out a clever way to sell donuts door to door that were probably Dale donuts.

So I would go door to door and sell these bags of doughnuts to people as part of little little devil doughnuts. So that was kind of my first job, because that was the only thing you could do. It was more lucrative than a paper route. Because in those days at 11, that’s all you could do. Right? And then in Alberta, where I grew up in Canada, you could start working when you were 12. And so I, which seems crazy now, but

Kelly:

I know I was thinking that.

Leonard:

So I did that from when I was 10 and 11. And then when I was 12, I started working as a busboy at a restaurant bussing tables at the age of 12. Like I had started working pretty much as a part of my regular routine since I was 10 years old.

Kelly:

Yeah. I mean, for me, it was eight. And you know, I had the good fortune that the money was not going to my family. But you know, it was the value of $1 that my parents really instilled in me. But I always find that the most successful entrepreneurs have done a stint in hospitality or the restaurant industry, because they have that ability to pivot and innovate. Would you agree with that? And if so, or if not, tell me why.

Leonard:

No, I do think there’s a connection, I think, whether it’s food service, hospitality, or sales. I think all of those kind of teach you the importance of human interaction and human relationships, and the most important skill set for an entrepreneur.

I mean, listen, entrepreneurship now is much more specialized, and it’s much more of a machine than it used to be, you know, back in the day, but I think the greatest skill you’re gonna have is persuasion. I mean, you cannot be an entrepreneur, it doesn’t matter how resourceful you are, it doesn’t matter how great the idea is, or how transformational it is. If you’re not able to persuade, you’re just, you know, it’s like having a car without an engine in it, it just doesn’t work.

So I think when you work in hospitality, or retail, for that matter, either, or it trains you to persuade, and trains you to understand how to convince people that either this is the right choice, or how to get better tips or how to sell this product. And that I think, was probably the most valuable thing for me, was my mum had a gift for that already. And I would say, if I really looked honestly at myself, it’s probably my only skill set is that I can take things that are complex, and make them simple, and persuade people to do things I would say that is my, those are my two superpowers.

The rest of it, I need partners to help with because, you know, there’s a million other skills that I can’t do, and I need someone to help with. And so I think that’s where that comes from. I think when you work, yeah, when you work at a young age, and you’re in the service industry of some kind, you learn the art of persuasion, because if you don’t you fail.

Kelly:

Right. Right. And I mean, I had the door to door experience, you know, selling raffle tickets for our church. And I think that is a great experience as well, because, you know, you learn rejection and resilience in real time. But, you know, one of your businesses really fascinates me, because of my background. I spent 10 years in corporate media, excuse me, 11 years from 1998-2009.

You have a business now called public, which is fascinating to me, because it involves citizen journalism, right? Why are you passionate about citizens and being able to be part of the media? I mean, I know from my perspective, but I’m really interested in hearing what you have to say about that.

Leonard:

Though, I should clarify, we sold that business about 10 years ago, okay. So that that business was exited, we sold it but it was doesn’t take away from why we were why I was interested in my partners were interested in doing it. So as I mentioned, my family was in the media business.

My uncle was really probably one of the most significant media moguls in Canada and the Commonwealth. And I got interested in it because You know, when you talk to him, he was a tax lawyer first. And then he ended up becoming a politician. And he ran the Liberal Party in Manitoba. So which is a province in Canada, and he was the leader of the opposition. And he sort of had this epiphany when he was sitting in government, which is that, in fact, it’s not really the government that has the power, it’s really the media. And if you can, effectively have a media voice, you have a lot more influence and persuasion. It’s the ultimate tool for persuasion.

I think I got interested in it from that perspective. And I also felt like, as the medium of the internet was changing how we consumed and created, there was going to be a model, where traditional break, we specialized in breaking news, by the way, that was mostly our area. And so we created a funnel by which, you know, if God forbid, you and I witnessed an earthquake, or a shooting or something, you know, a positive news event, you know, you and I were the likely people that were going to be breaking that footage.

There had to be a way to be able to standardize that and scrub it and get it into traditional media. So that, you know, we because we’re going to be where reporters can’t be. And that was the original premise for the public, and we were really one of the first companies in the world to commercialize the concept of citizen journalism. But, and I think, I’m not sure if this is still true, but certainly at the time, we were the only source of non unionized reporting into the Associated Press. Wow,

Kelly:

That’s amazing.

Leonard:

We were pretty pioneering and what we did, we ended up selling the company to the Anschutz group in Los Angeles about 10 years ago. Then I stayed on an earnout capacity with the interest group for a period of time running innovation and that kind of stuff. So that’s why I was interested in it.

I think it’s more true today than it ever was before. I mean, you can look at how we’re, how the media is creating incredibly divisive news. And the way we vote, the way we think about political extremes, misinformation, and all of the divides that are being caused now between human beings that weren’t before. And the same with how you treat social media. I mean, social media is the ultimate fragmentation of that. So I’m still super interested in what I do today. But yeah, we sold that company.

Kelly:

Yes, I did see that. And I was just, you know, as I was doing my research on you, I was wondering if you wish to still have it to influence the kind of information that the public is getting, because of all the things all the reasons you just expounded on.

Leonard:

Yes, I mean, I think the media is not a great business, unfortunately. But it’s a great business adjacent to selling things. So if you, you know, if you happen to have products and services that you’re selling, having a media engine bolted on to that is very valuable. So I think from a pure business perspective, probably not really, but from an altruistic perspective.

Having the ability to do that, again, more set up as a foundation, or something that was actually done as a not for profit, I think would be very compelling. And there’s lots of people now that are trying it, and playing around with it, like, some of the original Instagram founders just started a new company called artifact, which is trying to grade the quality of both what you’re reading, but also where it was referenced from and sources and stuff like that. It’s a pretty uphill battle, you know, the internet has created the ultimate form of human laziness.

Out of that, you know, when you’re on information overload, there’s only so much time you’re willing to put into deciphering the truth. And I can, that’s right now, the most important skill set you can have, both as an entrepreneur and probably a human alive today is critical thinking skills, the ability to understand how to think critically, and so I wouldn’t want to do it as a business, but I think I could definitely see myself getting back into it from a foundation perspective and a not for profit perspective. Sure.

Kelly:

Yeah. I agree with you. 100%. I mean, after being in the media, you know, and seeing both sides and seeing, I will tell you one, or the first news director, I had told me that I needed to remember the two R’s, ratings and revenue, and I will never ever forget that and when he told me that I thought, this is not the business for me.

So on another thread, one of my passions as an executive coach is really talking about resilience and how it’s the number one leadership superpower. I know you focus on the importance of bouncing back, why do you think that matters so much to the future?

Leonard:

Growth? Look, I think there when you think about people that are successful, so one of the things that I don’t like about internet culture today is just its amplified media, it is amplified, the old snake oil salesmen from, you know, the county fair by a factor of 20 million. And so everybody and their brother is claiming that they’ve solved problems, but how do you solve mental illness? How do you become a better person?

I’ve got the secret and answer for this. I mean, there are so many deceivers online that it’s almost unbearable, it’s unbearable to watch and listen to all these people that are false prophets. And it’s a, I think that in and of itself is probably one of the biggest challenges right now that civilization is facing, is you have an onslaught of people who are horrible false prophets that are claiming to be experts in fields that they’re not and claiming to give advice, and everybody now has a megaphone, that they can just blather out their opinions.

It creates a very dangerous situation, in my view, where truth becomes quite muddled, and people’s ability to people who really need help, and really need experts on getting the help that they need. And so when I look at, when I think about resilience, as an example, resilience is the core DNA difference between people that are successful and people that are not success being defined as internal happiness, because success, success means many different things to many different people. You know, some people are motivated by money, some people see success as their impact on other people, some see success as I got 4 million likes on a post today. And that’s success to them. I mean, however you define it.

Without resilience, you don’t get there. And I think it’s unfortunate, it’s an overused term that has become a little bit void for vagueness, not a lot of people really understand what it means or, but you know, my better half will ask me all the time, you know, did you have a good day today. And if you’re an entrepreneur, if you’re actually out in the world swinging, and you’re actually out in the world, as an entrepreneur, I should say, and this is maybe true, this is probably true for non entrepreneurs as well.

But I don’t think there’s such a thing as a good day or a bad day, they don’t exist. Because on any given day, I’m dealing with five dumpster fires. Five amazing things. The day is either net neutral or net negative net positive, there’s no such thing. It’s like it was an unbelievable day and everything went well, for every good thing, some massive shit mess just happened that I had two minutes before. That’s just, you know, brain curdling boring or bad or, and so I think, for me, resilience is the skill set that’s required to handle the inevitability of negativity, inevitability of problems, and being able to bounce, it goes back to what I was saying before about resourcefulness, those things are connected.

Resilience and resourcefulness are very connected, because you can easily be resilient, but not have the resourcefulness to be able to work around problems. Exactly. To me, those are the two, those are two gears of the same plane that you’re trying to land. And I think that’s where it matters, I think you have to be able, in order to be successful, meaning internally happy, you have to be able to navigate and manage the inevitable dumpster fires that are coming your way. And I think, I believe wholeheartedly that the rise in mental wellness issues and the rise in mental illness, particularly what I would call the lower spectrum and you know, things like depression and anxiety. I think a lot of that has come from a societal loss of resilience and the ability and I and listen, I have no science or data to back that up. But my inclination is that it is the ultimate form of resiliency, which also would result in a lowered EQ so that I’m not saying it’s all positive, right. Look at our grandparents’ generation. They lived in the confines of war and in the confines of rationing. They did not live in a world of abundance. In a world where you are surviving, sometimes two world wars, you know, let alone one. And you’re not in a world that is abundant.

Your ability to be resilient is inherent in the DNA because you can’t survive without it. But the farther you get away generationally from restriction to abundance, resilience begins to decline. And as resilience begins to decline, you start to see a rise in mental wellness or mental illness that are directly correlated to a lack of resilience. And I think those things are mapped, they’re correlated for sure.

Kelly:

Sure, yeah. And, you know, you made me think of my grandfather, who was a doctor for the US Army during World War Two, he retired as captain. Listen, I’m an executive coach for high ranking officers in the military, and every time I tell them this story, they’re like that didn’t happen. And I know it didn’t, my grandfather made this story up, because he didn’t want to talk about the trauma. Anytime I asked him what happened, he would say we hit on a bluff in Normandy over the Japanese camp. And when they fell asleep, we blew up helium balloons and tied a grenade to one end, floated it over, and blew them up. That never happened, that literally never happened. But it was his way of covering up the pain, because they didn’t want to relive that because of the PTSD.

While every generation has its problems, they really were the most resilient. I remember, my grandmother (his wife) would save foil, you know, because it was a throwback to when they did rationing. And they did save things. I think while we all have issues, and I’m not, you know, downplaying that, I think we do all live a soft life, because resilience really does teach you who you are, you know, I mean, I did a whole TED talk on how I went through through sexual assaults and in college within two months of each other, and how, you know, while that is horrific, and I would never want to go through it again. I mean, I survived the worst. And I’m still here, you know, so throw it at me, because I’m probably going to survive it.

Which kind of brings me to my next question, because I find that people can resonate more with your failures than they do with your successes, and you’ve been wildly successful. But there have to have been some missteps in your career. So would you be willing to share what was your biggest, most painful failure? And how did you recover from that?

Leonard:

Yeah, I mean, listen, I by the way, before I answer the question, one thing I did want to mention is before we leave the topic of resilience, yeah, you know, I often get asked, and my family’s Jewish, and my family are both survivors and not survivors of the Holocaust. And we lost at least three quarters of our family on both sides. And you often get asked, I think, or I think these questions are earnest. Meaning Why do you hear so much about the Holocaust? Like why is there so much conversation about why there’s so many movies about it? And there are two answers to that question.

One answer is that, in the grand scheme of genocide and history, it is unlike anything you’ve ever seen before there was no, there is literally no modern map, or anything that occurred in the Holocaust that occurred in other genocides not not two way one is worse than the other, they’re actually very different. What made the Holocaust unique? Were a bunch of components that made it worth studying much in the way the uniqueness of other genocides make it worth studying. But this was particularly unique in the way it was executed.

But secondarily, the reason that people talk about it so much, is because it is a living experiment with people that are still alive today about how you take the absolute worst moment in humanity, the lowest ebb in a possible human’s life, you know, not just war, not just this is human experimentation, separation from family, social experimentation, starvation, slavery, I mean, take everything bad in a bucket, and then talk to someone who is still alive, to speak about those events. And I think that that, if you really want to talk about resilience, one of the greatest lessons you can learn is speaking to Holocaust survivors that are still alive today before, you know because many of them are now in their late 80s and 90s before they pass away, because it is the ultimate testament to both those that were resilient and survived and those that just even though they survived the war and survived the Holocaust could not turn their ships right again.

When you look at both of those scenarios, you see really unbelievable stories of resilience. And I think it’s, it’s, it’s very valuable to look at those those case studies and those people today before they pass away, but to your because I don’t think there’s a better human, there’s no better human case study of the story of resilience than people that came out of the Holocaust. If you understand it,

Kelly:

Yeah. I grew up in South Florida, about an hour north of Miami, where there’s a vibrant Jewish community and my family’s Italian. And I feel like Italian mothers and Jewish mothers are just like, a jump from each other. And fortunately, I had the opportunity to speak to a lot of Holocaust survivors. And you’re, you’re right, I’m a testament to everything you just said. I kept thinking, as as I was listening to you about that Viktor Frankl quote from A Man’s Search for Meaning, you know, between stimulus and response, there is a space and that space is our power to choose our response. And in that response lies our growth in freedom.

The Holocaust survivors that I had the good fortune of speaking to, were surprisingly positive, you know, really about the future. And I think seeing the worst of humanity really makes you can go one of two ways you can go the dark way, or the way of the light, which is what I had the good fortune of experiencing from them. And I’m grateful that I was able to, to witness that and bear witness to their journeys in that small way. And also, let me say, I’m very sorry for your loss. I mean, I am studying generational trauma, you can, you can see that play out, especially when it’s not resolved.

Leonard:

I know this, and I want to answer. I appreciate it, I want to answer your question because of your own failure. But I do feel like we are at a time limited scenario where the greatest case study and resilience is still available to be done. And the story is still being told and recorded. And there’s lots of information in the show off foundation and stuff where you like if you’re really a student of resilience, and you’re really interested in that, there are very few better case studies than that just because of the unique nature of the event and how it happened.

But to answer your question, I again, I say this to people all the time about failure, I fail constantly. And I don’t like when entrepreneurs. I think now entrepreneurs say that because they think it’s fashionable to say it. I’m saying this because it’s true. Like yeah, I fail multiple times a day, I make the wrong decisions, I bring in the wrong people, I focus on something I shouldn’t focus on that failure is. emblazoned in my daily schedule, I do it all day long. And other times, sometimes it hurts and gets a bit more under your skin more than it does other times, especially when the impact of that failure impacts other people and impacts other people’s lives. It’s obviously a little bit more frustrating.

But I think for me, there’s no one colossal failure that stood out because, for me, my life has a trail of failures and regrets. I always hate when people say, Oh, I’ve lived my life and I have no regrets. Well, you’re just a liar. Like, if you haven’t lived with regrets, not paying attention, or you’re not genuine, or you’re not making real decisions. I mean, I have, I can think of 100 regrets that I have that are big ones that decisions I should have made differently. And so to pinpoint one particular one, I think would be difficult, I mean, one of the biggest.

So I’m choosing to think of this as regret rather than failure because failure is, to me, much more tactical. And there’s lots of examples of times where I’ve made just stupid, shitty decisions and failed at something. But regret is a much more painful and long lasting emotion. And so I have tons of them. You know, for example, I wrote one of my greatest regrets is that I didn’t serve in the Israeli military. I don’t talk about it very often. It’s not like that but it’s something that eats away at me every day that I should have done and left high school and gone and done service for two years. And I think I would have it.

There’s a piece of me that feels incomplete because I didn’t do it. And, and that was my no one’s decision but my own really I could have done it if I wanted. But I just got caught up in the treadmill that is University and law school and you know. So that’s a big regret. And I think failure and regret and understanding the difference between those two things is really important because one is a tactical outcome, and others an emotional response. And I have lots of failures that I have no regret about, and lots of failures that I have regret about. Yeah. And so that’s really powerful. I think it’s just the question of how you emotionally weigh failure.

So when you talk about one of the great illnesses that’s plaguing American entrepreneurship, is this discussion where people are just not honest. Let me take a step back. It’s interesting in entrepreneurial circles in the United States, it’s starting to replicate the polarization of general society in the United States. So you have the entrepreneurs who, when you ask them, how’s it going, they say, “I’m killing it.” That’s unbelievable. I know it’s not true.

So whenever somebody says to me, “Oh, we’re killing it,” I tune out instantly. I know, this person is not being real, and I don’t want to hear it, and I don’t care. Yeah. And the opposite is true, where you have a lot of entrepreneurs that are too connected and wallowing in negative emotions where all you know, they’re over exaggerating, it’s lonely at the top. And mental illness is more prevalent, and it’s the entrepreneurial community. So either one of those two camps are gray and confusing.

So I think for me, I care and want to associate with people that are entrepreneurs, that are intellectually and emotionally honest. So when an investor asks me how things are going, they are never ever going to get an answer for me that like we’re killing it, they’re gonna get, they’re gonna get a balanced answer. Here’s the good stuff. Here’s the bad stuff. Here’s the stuff we’re fixing. And here’s how we’re dealing with the bad stuff. And that I think is, is when you think about failure. That’s I think the distinction is failure is part of your toolkit. It’s part of your every day regret in association to that failure. Is the question that you always haunt, you know, you hate yourself with that, whether or not you regret that failure. And so I have lots of failures that I regret lots, I mean, on a personal front on, but there’s no one other than what I said about the Israeli military, where I feel like it’s a consistent eating away at me.

The only other thing I would say, and I’m sure other entrepreneurs have experienced the same thing. I think one of the regrets attached to failure that I have is decisions made around timing. You know, part of the art of doing any entrepreneurial ventures is understanding timing, it’s understanding how to get in and how to get out and it’s such a hard skill set. You know, so much of it is luck. And so much of it is just, you know, I always talk to people about zoom, every vehicle we’re on today.

There was nothing unique about Zoom; there was Skype and lots of other video conferencing systems. And as COVID kicked in, you know, obviously, they were in the right place in retirement it just ballooned. Right, it became a household brand. And now we’ll see, you know, how the company takes advantage of that. But could you ever plan for that? No. And, and you look at other companies that had offers to sell, and didn’t, and then the company declined, and they lost the market value. So to me, it’s always about timing. Yeah. It’s understanding and having the foresight to know when to make decisions, that you feel like you’re on the right side of history and the right side of time.

Kelly:

Yeah, thank you for all that, you know, it’s, I can’t tell you how many entrepreneurs that I speak to, you know, and we’re, our team is small but mighty, and they, you know, we fail all the time. I mean, it’s and usually my question after that is, what do we learn from it? And what are we not going to replicate it again? And so thank you for being honest.

Because I can’t tell you how many times I hear some entrepreneur telling me they just hiked Mount Everest and their businesses are on fire and they’re, they’re killing it. And it’s like, really, are you? You know, because at the end of the day, we’re all failing and we’re all succeeding at the same time. Like you said, it’s dumpster fires. So that’s part of the entrepreneur lifestyle. And you’re right about the timing as well.

What’s your favorite part of the work you do? Like what really lights you up inside?

Leonard:

You know, for me, there’s probably a couple things. One is something I don’t like. I don’t like being confined to a routine or confined to having to wear a certain kind of clothes. I will not wear a suit ever again. When I left the practice of law, the sign for me of success in my life was I can wear what I want, at whatever meeting. Like I do a lot of public speaking and stuff, and I’ve spoken at the United Nations and the G8 in a T-shirt and jeans. And that’s all I ever wear. And it’s stupid, but it’s, for me, it was a sign that I’m in control of my own destiny in my own life. And I think for me, that was super important.

Because so one of my favorite things is just knowing in my gut, that I am the master of my own domain and my own choices. And that’s super important to me, freedom, not just financial freedom, but just freedom generally, is a huge driver. For me, it’s a massive driver for me. And I think the other part of it that I really like is that I am most useful in being able to identify opportunities at the right time.

So I get excited when I can identify a market opportunity that is timed well meaning like, I feel like it’s easy to say in 20 years, this is going to be something interesting or this is going to be a market opportunity. But I like the idea of being able to look around corners and find things that are interesting opportunities that will inevitably be equitable companies doing that on a regular basis.

But I’m not the kind of person I’m not the guy you want in the business when it’s 50 million in revenue. And you need adults in the room at that point, which I am not. So I’m much better at identifying you know, we talked about the showerhead earlier. Yeah, yeah, that was an example of us identifying a real you know, that business, the business called Hai, Hai. And it was a moment in time where we looked at trending that was going on in the home, during COVID looked at data around the importance of that experience to people, but also the impact of the environment, you know, we we are going to run out of water on this planet long before we burn up.

After agriculture, you and I are the biggest abusers of water. And one of our biggest abuses in the home, if not the largest inside the home is your shower. And so when we looked at all of that, just piecing that opportunity together is the stuff that I love, like taking something from nothing and putting together a strategy and a business, knowing that you’ve got it at the right time. Or you feel like you’ve got it at the right time. That’s the stuff that I love. Yeah, the rest of it is part of the price you pay for the privilege of doing that.

Kelly:

Yeah, I agree. So if you could go back to your very first business that you started as an entrepreneur after being a lawyer, what advice would you give yourself sitting in the seat today?

Leonard:

Looking backward. So this, this is a conversation I have with young entrepreneurs all the time, I think the the the best advice that you can give a young entrepreneur is that no one talks about where people fail in their entrepreneurial journey is their inability to map the desired outcome in their personal lives to the style and type of business that they’re building. Yes. And the reason so if you took the Gen pop of entrepreneurs, the failure rate is 80 to five to 90%.

But if you looked at the success rate or failure rate in the immigrant community, it’s significantly better, like failure rate is much lower an immigrant run early stage businesses and and in that I’m talking about sub from a Subway franchisee to running a dry cleaning store, to the person building a software company in our startup anyone in that universe. Although I do think they are different. I think there is something very different between owning a small business and being an entrepreneur. They’re very different things.

However, the success rate in immigrant-run small businesses is way higher than the general population. And I believe the reason is because when you ask an immigrant to this country or anywhere in the world, why they’re doing it, why do they have the dry cleaning store? Why did they start a Subway franchise? Generally you’re gonna get three answers.

The first answer was because they were unemployable or had difficulty getting employment. But the two biggest drivers are they wanted a roof over their family’s head and they wanted to educate their children. So when the dumpster fires happen, and the inevitable shit hits the fan, the sturdiness of connecting the reason you’re doing that as a business, so the life outcomes allows you to stay much more grounded and much more resilient around why you’re doing this every day. Because they’re paying for their kids’ education. They’re putting a roof over their heads. They may have been a doctor in Jordan but came here and don’t want to be a janitor, they’d rather do their own stuff.

I think at the end of the day, the more people that can connect the life questions about how they want to live their life to the kind of business they’re building the more successful the house. So do I want children? How much do I want to be traveling? Do I want people reporting to me? How much money do I really need to be happy?

Because there is a massive law of diminishing return on money, you know, once you hit a certain cliff, for each individual, that every dollar becomes a burden after that, right? And so if you can honestly answer those questions, and sometimes you don’t know the answers, but if you can at least be constantly thinking about them, you’re gonna have a much more successful entrepreneurial journey than someone who doesn’t answer those questions. Yeah, and

Kelly:

I agree with you. As a coach, one of the things I always connect with my people is, What’s your reason why? What’s your purpose? Because when things get rocky in life, whether you’re an entrepreneur or a high ranking officer in the military, you need to have that sturdy foundation of something bigger than yourself, whether it’s putting a roof over your family’s heads, educating your children. And you’re right, I mean, you’re exactly right. So one last question, then we’re gonna go into rapid fire, which are more fun questions.

What has been your favorite launch through caravan? Are you able to talk about that?

Leonard:

You know, it’s, it’s kind of like asking to tell you your favorite kid. Right? Look, I would say just because we already talked about it, let me continue on with the analogy, just because it’s right. I was very involved in the day to day and still am. I think that was an incredible experience in taking something to market. That meant, I’ll give you an example, we got interested in the shower market. Because when you ask, if I asked you, if I gave you a lesson to tell me your most important self care tools in the home, and shower was not on that list, you wouldn’t think to put shower on it. But the minute I put a shower on it 87% of the time, it would be your number one or number two choice.

Then when you start to look at why there’s been no innovation in that space, one of the key insights is there’s no innovation, because there’s no electricity in there. And because there’s no electricity in there, there’s only so much you can do with mechanical engineering, to be able to make that interesting. And so we literally took that whole analysis, and we produced a company that is the only appliance in your home, that makes its own energy, we basically turn your shower into a teeny, tiny Hoover Dam, that takes the power of the water stores that in a turbine, the energy it creates, and a turbine and a battery. And we use that to power Bluetooth and Wi Fi.

Why? Because we can inevitably use that data to one make your experience better, and to more importantly, to cut your water resource usage in a way that makes your experience 10 times better, but allows you to cut back. Like if I put one of our units in your home, I’ll reduce your water usage by 34% and your electrical use by at least 22%. And we do that all through behavioral training. And so that launch was incredible. And inevitably what we’ll do with that, I mean, I can’t say too much about it. But there’s going to be we are going to make very good use of the water and the energy you’re saving. And there’s a much bigger societal plan behind high and that business. And so that was a great launch where we could do something great for you, and great for the planet at the same time, but also changed the way an entire industry worked.

Kelly:

Yeah, I mean, that when I read about it, I was like, How do I not know that this and I mean, one of my favorite things to do is shower as self care, you know, I mean, I’m in an emotionally laborious job. And one of the things I’ll do at the end of the day is just shower the day off. So I love that and thank you for sharing.

I love this conversation and it’s been very enlightening and hopeful. I really appreciate your time but I always like to ask these four questions. So I hope you’ll indulge me just a little bit longer.

What is your favorite food?

Leonard:

Oh, for sure. My mother makes this Jewish thing called commish, sprites, which is kind of like a Jewish Piscotty and matzah ball soup. Those would be my two.

Kelly:

I understand, you know, because we have a lot of Jewish friends and we just went to our first Passover dinner that there are two theories about matzah balls: one that sinks and one that floats. Which is your favorite?

Leonard:

I’m a sinker. Okay, well, I don’t like the floaties. I like the hard dance of sinking matzah balls. Yeah. The great sinker floater today.

Kelly:

I know, I didn’t realize it was a whole thing. What books are on your nightstand?

Leonard:

Surprisingly, not a lot. I mean, I, one of the downfalls of the internet in my life is it has made my attention span so short that if it’s longer than 20 pages, I don’t read it anymore. So I read a lot of academic journals and a lot of academic articles.

I never, ever enjoyed reading fiction, it was just not my thing. If I wanted escapism, I wanted to watch it, not read it. So 90% of my reading is academic journals, and economic debates on recessionary and stagflation. And so I tend to read more of that. So my reading pile is predominantly academic journals that are tied to macroeconomics and sales theory and financial stuff. So I’m a little bit boring that way.

Kelly:

No, that’s fine. So what songs are on your playlist?

Leonard:

Interesting question. I tend to be a little bit nostalgic in my music these days. So I grew up in love with a band called The Jam, which was a band from the 70s in Britain, and listening to a lot of that, and then I would say, more modern stuff. I’m a very big fan of a band called Manchester Orchestra. I’m a big, big, big, big, big fan of Sufjan Stevens and Iron Wine. And I like a bit more of the Americana stuff, even though I’m Canadian.

Kelly:

I love that. I love that. Okay, last question.

What are you most grateful for at this moment right now?

Leonard:

You know, I would say it is a hard question to answer, obviously, but I would say I feel very lucky to be alive in a moment where I get to see the beginnings of a true technological evolution. I think, actually, I would say two things. One, I feel very fortunate to be alive historically, in a moment when the State of Israel exists. And because I don’t know that it will be there forever. And so having been able to have been alive in a moment where you can witness it, and experience it, for me is very special. And I would say very grateful for being around at a time when you’re starting to see real technological evolution and real change and being able to experience the rise of electric vehicles and autonomous vehicles, and conversational and generational AI. And all of that stuff is just super interesting to me. And then thirdly I’m super grateful for my family and friends and my better half Sarah, and just the ability to share those things with people that you care about. And I think those are the three things that I probably feel the most grateful for.

Kelly:

Thank you so much. And if somebody wanted to get in touch with you, whether it was an entrepreneur or you know, a business that maybe is not killing it yet, but could be with your help, how would people do that?

Leonard:

Connect with me on social media!

Kelly:

Thank you so much. And thank you to the audience for listening. It’s our intention on Hidden Human to inspire you to go out and have authentic real conversations to deepen the connections in your life. Thank you so much, Leonard, thank you to the audience and make it a great day.

Leonard:

Thank you so much.

Kelly:

Thank you!